Metropolitan Dionysios of Servia and Kozani †

From its earliest years, the Church has honored martyrs in blood and martyrs in conscience. ‘Martyrs in conscience’ were saintly monastics and ascetics who lived in the wilderness. There’s a difference between monastics and ascetics. Monastics are those who live all together in large coenobitic monasteries, while ascetics or anchorites live in isolation in secluded, inaccessible caves. Both monastics and ascetics are people who have left behind worldly matters and have dedicated themselves to something better and more perfect. These are also the people of whom Saint Basil the Great wrote: ‘they proved to have greater than human capabilities’. One such was Saint Theodosios the Coenobiarch, the memory of whom the Church keeps today.

Saint Theodosios was born in 423 in a small town in Cappadocia, to devout parents, who taught him Christian virtue through their advice and example. From childhood he showed particular interest in Church matters and was ordained reader. When he attained a certain age, he left his homeland, his parents and friends, and visited the Holy Land. On his way to Jerusalem, he went to see Saint Symeon the Stylite, who, when he saw him, greeted with ‘Welcome, servant of God Theodosios’, as if he knew him. Saint Theodosios received the blessing of the great ascetic and continued on his way to the Holy Land. In Jerusalem he found a fellow Cappadocian, an ascetic, and lived with him for a while.

From the outset, Saint Theodosios showed such asceticism and virtue that, in a short time, he’d acquired a reputation, and others who, like him had chosen the path of asceticism, began to flock to him. His cave was atop a mountain and the saint lived hidden away there until gradually it became a monastery of many monks, who formed a brotherhood. Saint Theodosios taught and trained them not only in prayer and work but also in the remembrance of death. Remembrance of death is of prime importance for monastics. Monks and everyone else have to remember that we’re mortal and that one day we’ll die, as Saint Paul writes: ‘For we who are alive are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake’ (2 Cor. 4, 11).

Coenobitic monasticism is the model of communal life, like that of the earliest years of the Church, as described in the Acts of the Apostles: ‘The heart and soul of the believers were one, and nobody claimed any possession as their own, but rather all things were common to them’. This testimony from the book of Acts is one of the most controversial issues of our day, but is also the model and basis of coenobitic asceticism. It was rightly said that ‘the communal/coenobitic way of life, will, throughout the centuries, be the genuine way of Christian existence in the world. And that way has been preserved to this day in the monastic coenobium, which remains the model of Christian society’. Not that everyone should become monastics, but that they should take their example from the life of the monastics.

When Saint Theodosios saw that men were arriving, he built a large monastic complex with workshops, a hospital, a hospice and three large churches. The monks, who numbered about 700, had come from Greece, Arabia, Armenia, Persia and the Slav lands. When they were sick, they were treated in the hospital and, in their old age, were looked after in the hospice. They read the services separately in their own language, though they gathered all together in the largest church for the celebration of the Divine Liturgy. Such organization and such a perfect image of the communal life command our admiration, as well as our sorrow over the number of wars that have been fought over social issues, because such examples and models from the tradition and life of the Church have been ignored.

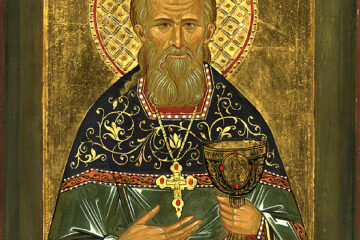

The great coenobium of Saint Theodosios, which was so wonderfully well-organized, was truly a paradise on earth. The Patriarch of Jerusalem was a great admirer of this monastic polity and appointed Saint Theodosios to be the general overseer of all the coenobia in Palestine, which is why he’s known as ‘the Coenobiarch’. But Saint Theodosios also worked against heresies, and, as a result, fell out of favor with the heretic emperor, Anastasios, who exiled him. After his exile, the Coenobiarch returned to his monastery where he lived for another 11 years, until 529, when he departed this life at the age of 105. Well into old age, Saint Athanasios was a fine figure of a man, of imposing stature. The words of Saint John Chrysostom certainly apply to him: ‘it’s not only the words, but also the very faces of the saints that are filled with grace’. Amen.

Source: pemptousia.com

0 Comments