Metropolitan Kallistos Ware of Diokleia

Am I not free?

(1 Corinthians 9:1)

God persuades, He does not compel;

for violence is foreign to Him.

(Epistle to Diognetus VII, 4)

What Shall We Offer?

In an Orthodox hymn used at Vespers on Christmas Eve, the Virgin Mary is seen as the highest and fullest offering that our humanity can make to the Creator:

In an Orthodox hymn used at Vespers on Christmas Eve, the Virgin Mary is seen as the highest and fullest offering that our humanity can make to the Creator:

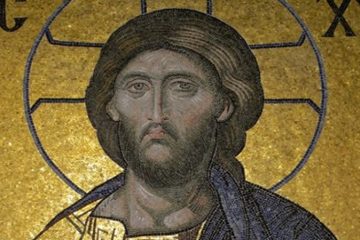

What shall we offer You, O Christ,

Who for our sakes have appeared on earth as human?

Every creature made by You offers You thanks:

The angels offer You a hymn,

The heavens a star,

The Magi gifts,

The shepherds their wonder,

The earth its cave,

The wilderness the manger;

And we offer You a Virgin Mother.

Theotokos (Mother of God), icon, Monastery of Sinai, 13th Century

As our supreme human offering, the Mother of God is a model — next to Christ Himself, and through God’s grace — of what it means to be a person. She is the mirror in which we see reflected our own true human face. And what she expresses, as our pattern and example, is above all human freedom. “Am I not free?” asks the apostle; and Mary shows us precisely what this liberty implies.

Freedom, the capacity to make moral decisions consciously, with a sense of full responsibility before God, is what most of all distinguishes the human from the other animals. In the words of Søren Kierkegaard, “The most tremendous thing granted to human persons is choice, freedom.”[1] Without liberty of choice there is no authentic personhood. When God says to Israel, “I call heaven and earth to witness against you this day, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse; therefore choose…”[2] He offers us a gift that is difficult to employ aright, often bitter and painful, even tragic, yet without which we are not genuinely human. It is freedom of choice, more than anything else, that constitutes the image of God within us. This has of course to be qualified. Divine freedom is unconditioned, whereas our human freedom in a sinful and fallen world is restricted in all too many ways. But, though restricted, it is never totally abolished; it remains in some way irreducible and inalienable.

Let us explore together the nature of this freedom, essential to our human personhood, which the Blessed Virgin Mary displayed to a preeminent degree at the Annunciation.

Response in Freedom

In the view of Karl Barth, it is a fundamental error to imagine that at the Annunciation Mary is making a decision on which the salvation of the world depends. To see in Mary, so Barth argues in his Church Dogmatics, “the human creature cooperating servant-like in its own redemption on the basis of prevenient grace” is a heresy to which No, “must be uttered inexorably.” We are to understand her role at the Annunciation, “only in the form of non-willing, non-achieving, non-creative, non-sovereign man, only in the form of man who can merely receive, merely be ready, merely let something be done to and with himself.”[3]

The approach of the Christian East is altogether different. In the words of the fourteenth-century Byzantine lay theologian, St. Nicolas Cabasilas:

The Incarnation of the Word was not only the work of Father, Son, and Spirit—the first consenting, the second descending, the third overshadowing—but it was also the work of the will and the faith of the Virgin. Without the three divine persons this design could not have been set in motion; but likewise the plan could not have been carried into effect without the consent and faith of the all-pure Virgin. Only after teaching and persuading her does God make her His Mother and receive from her the flesh that she consciously wills to offer Him. Just as He was conceived by His own free choice, so in the same way she became His mother voluntarily and with her free consent.[4]

Cabasilas perceives the all-important contribution made at the Incarnation by the created human freedom of the Virgin. “God persuades, He does not compel”: the statement in the Epistle to Diognetus applies exactly to the event of the Annunciation. God knocks at the door, but does not break it down: Mary is chosen, but she herself also makes an act of choice. She is not merely receptive, not merely “non-willing, non-achieving, non-creative,” but she responds with dynamic liberty. As St. Irenaeus expresses it, “Mary cooperates with the economy”[5]; she is, in St. Paul’s words, a synergos, a fellow worker with God—not just a pliant tool but an active participant in the mystery. What we see in her is not passivity but engagement, not subordination but partnership, not submission but mutuality of relationship.

All of this is summed up in Mary’s reply to the angel: “Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word.”[6] This reply was not a foregone conclusion; she could have refused. Violence is foreign to the divine nature, and so God did not become human without first seeking the willing agreement of the one whom He wished to be His mother. As Pope Paul insists, in his notable doctrinal statement Marialis Cultus (2 February 1974), Mary is, “taken into dialogue with God,” and she, “gives her active and responsible consent”; we are to see in her, not just a “timidly submissive woman,”[7] but one who makes “a courageous choice.” She is a decision maker. It is a striking fact—on which we can never reflect too much — that, whereas the creation of the world was brought about solely by the exercise of the divine will, the re-creation of the world was set in motion through the cooperation of a young village woman engaged to a carpenter.

(to be continued)

Notes:

1. Journals, translated by A. Dru ( Oxford, 1938), § 1051.

2. Deuteronomy 30:19.

3. Vol. I, part 2 ( Edinburgh, 1956), pages 143, 191.

4. Homily on the Annunciation 4–5; Patrologia Orientalis 19, 488.

5. Against the Heresies 3.21.7: PG 7, 953B.

6. Luke 1:38.

7. § 37.

Source: pemptousia.com

0 Comments