James W. Lillie

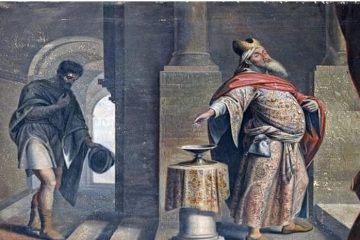

Another point of interest is that the church of Saint Dimitrios, for 60 years (1430-1490) remained as part of the local Church, when almost all the other churches in Thessaloniki had been turned into mosques after the fall of the city to the Turks in 1430. This was because the governor of the city, Loukas Spandounis, paid a great deal of money to the conquerors to prevent the church becoming a mosque. In order to honour this great benefactor, after he departed this life, the church allowed a Renaissance-style sarcophagus containing the body of this benefactor of the Church and nation to be placed in the N.W. wall of the central nave of the church.

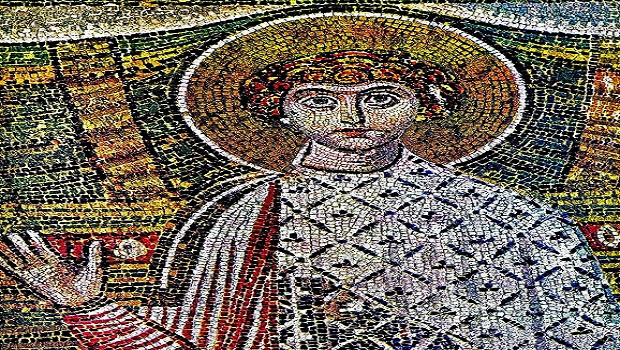

Saint Demetrius, byzantine mosaic from his church in Thessaloniki, 8th Century

In the end, though, the church was, in fact, turned into a mosque in 1491, in the reign of Sultan Bayazit II, and given the name “asimië tzami”. It remained a mosque until 1912, when Thessaloniki was liberated by the Greek army on the feast of Saint Dimitrios (26 October).

Professor Bakirtzis also notes that from the accounts of the miracles, we know that various categories of patients were looked after in the basilica of Saint Dimitrios: the paralyzed governor Marianus; the governor with an issue of blood; citizens of the town with serious ailments, such as malign temperatures; bubonic oedemas; expulsion of blood; psychiatric problems, such as the possessed soldier; the hemiplegic governor, and so forth.

The sarcophagus containing the body of governor L. Spandounis, a great benefactor of the Church

The patients were taken to the church on stretchers by their kith and kin, either on a sling or simply in their arms. This means that there was no ambulance service and that the treatment rooms for the patients were either in the basilica itself or in some adjacent building.

Once the patients arrived, the church attendants provided each of them with a mattress for a bed. Treatment also included proper nourishment and hot baths. Relatives did not stay with the patients overnight, which means that the basilica must have had auxiliary nursing staff for the night shift, probably on a voluntary basis. There is no record of any charges ever being made for treatment. Patients stayed in a single room and many miraculous healings were attributed to visits from Saint Dimitrios.

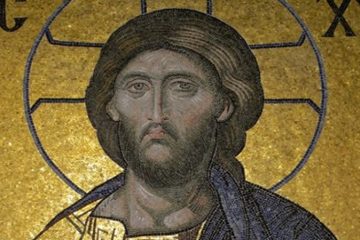

Votary mosaics have survived through which successfully-cured patients expressed their gratitude. One such, for example is the mosaic on the northern column of the sanctuary with the inscription, “I, Klimis, without hope from other people, but restored to life through your power, have dedicated this out of gratitude” (Ch. Bakirtzis, The Miracles of Saint Dimitrios, pp. 368-9).

For centuries, the holy relics of the saint were kept in the church, but at some point they were taken to the West, perhaps at the time of the Crusades or even later. The people of Thessaloniki were unaware of the destination of the relics until the archaeologist, Maria Theokhari discovered them in the Abbey of San Lorenzo in Campo, in Italy.

Afterwards, the archeologist in question presented a paper on the subject to the Athens Academy (June 1978) and the then Metropolitan of Thessaloniki, Panteleimon II, became extremely interested. He set in motion a process for the repatriation of the relics. His request was favourably received and, on 23 October, 1978, the skull of the saint was returned, the rest of his relics following two years later. The finely-worked silver reliquary lies within a marble ciborium in the northern nave of the church.

Anyone visiting Thessaloniki and the church of Saint Dimitrios can buy a very interesting little book, Our Saints, by Fr. Asterios Karabatakis, which is an account of all the saints whose relics are in the church.

Read the first part here

Source: pemptousia.com

0 Comments