Archimandrite Varnavas Lambropoulos

A superficial reading of the epistle for the 6th Sunday of Matthew gives the impression of dry moralism. The apostle twice repeats the exhortation to the faithful to learn to take the lead in the performance of good deeds, which he considers to be examples of spiritual productivity. And once he counsels them to avoid heretics ‘after one or two admonitions’.

True or merely useful?

The obvious question arises, one which is often posed by many people: ‘Why should I be a Christian, especially Orthodox, and have to avoid heretics, since I can still be a good person without being a member of the Church? Are there no people of other persuasions, other religions, and even atheists, who have a great deal to show in terms of good works?’. Asking this question is tantamount to saying: ‘I’m not interested in whether Christianity’s true or not. All that concerns me is whether it helps me to be a good person. My criterion isn’t its truth but its utility’. But the value doesn’t lie only in the fact that it’s useful. The Christian faith isn’t merely a system of morality. As the leading Orthodox theologian Georges Florovsky emphasizes: ‘The Orthodox faith is a theology of events’. It’s testimony to facts. If these events to which Christianity bears witness are simply tall tales, then no honest person should want to believe in them, no matter how useful they are.

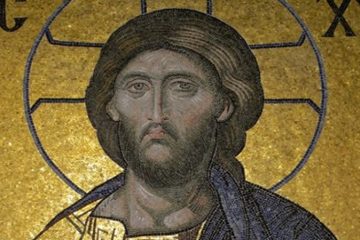

When, in today’s epistle Saint Paul urges Titus to speak to the faithful with certitude and authority concerning what he’d written earlier on in the letter, he’s not referring to moral precepts, but to the fact of salvation in Christ. This is to say that in historical time and place, the divine and human natures were united in Christ, without confusion or separation. Without ceasing to be perfect God, Christ became a perfect human person, ‘without sins’. He thus made it possible for us not merely to become better people, but to be renewed, to become new people, and heirs to eternal life. This redemptive truth was proclaimed by the holy Fathers who constituted the 4th Ecumenical Synod in Chalcedon. Today we celebrate their memory. At sixteen sessions, in October 451, they arrived at unanimous decisions, after fruitful discussions.

Heresy: separation from God

Naturally, these discussions were in no way related to the senseless conversations which Saint Paul advises Titus to avoid. These are ‘foolish controversies’ (Titus 3, 9) which end in profitless bickering and squabbles about issues in Judaic law. They were caused by Judaizing Christians who were attached to the letter of the law, who insisted on retaining the force of this imperfect and precursory law in the time of the perfect law of the Gospel and the revelation of salvation in Christ. Naturally, this led, if not to the abolition, at least to the alteration of the life of the Church. In the end, it led to heresy. It follows, then, that for Saint Paul and the Fathers of the Church, ‘heresy’ isn’t simply a theoretical difference of opinion. It’s an erroneous way of life. Even if it may be a morally upright life, as regards the externals, it’s false, because it’s severed from the saving truth and unity of the one Church. Many of the heretics lived very strictly and were morally beyond reproach. But Christ said that, on the Day of Judgement, they would hear ‘I do not know you’, even though they’d been allowed to prophecy in his name, to expel demons and to perform many miracles (Matth. 7, 22-23). This is what Abba Agathon had in mind, in the Book of the Elders. He accepted without complaint the accusations that he was proud, a fornicator, a gossip and a chatterbox, but when they called him a heretic, he bridled and said: ‘I’m not a heretic’. When they asked him why he couldn’t bear this designation, he replied: ‘The first ones I attribute to myself and are for the good of my soul, but to be a heretic is separation from God; and I don’t want to be separated from God’. For Abba Agathon, separation from God wasn’t separation from a subjective concept concerning God, but from the saving truth of the one Church, that is, separation from real Life.

The responsibility of admission into the Church.

No shepherd of the Church should be indifferent to such a deadly separation of one of his flock, and he should try, with repeated exhortations, to bring the deluded person back into the fold of salvation. The limit of the two efforts, as set by Saint Paul, clearly shouldn’t be taken literally. The conversion of Saint Augustine certainly wasn’t the result of a couple of admonitions on the part of Saint Monica. And the Jewish doctor of Saint Basil didn’t become Christian after only two or three conversations with the saint. What Saint Paul wants to point out is simply that an experienced shepherd has the discernment to know when to stop trying to ‘draw back in’ the deluded or fallen member, because this would be ‘flapping against the wind’, according to Saint John Chrysostom. Then, of course, those who persist in their delusion condemn themselves, because they no longer have the excuse that nobody counseled them.

So today’s Epistle reading is anything but a excerpt from a manual on morality, because it reminds us of the purpose of Christ’s incarnation, which isn’t simply our moral improvement, but our induction into his one Church, that is our deification by grace and eternal salvation, for which we’re entirely responsible.

Source: pemptousia.com

0 Comments