By Fr. Michael Psaromatis

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia

The small open boat climbed another wave and dropped into its trough with a shudder. The island had disappeared. Grey sky and broken sea surrounded them, and the Jesus Prayer rose quietly between clenched teeth. The larger ship that had carried the missionaries from island to island was now far behind them. In its place was this little craft, rising and falling between the swells as though suspended between sky and water.

Wind pulled at clothes and hair. Salt stung the eyes. Each plunge of the bow brought a rush of water over the deck. The boat rose again as if lifted by an unseen hand. In that moment, human certainty felt small, while the cry of the heart opened wide. The bishop prayed aloud, entrusting the journey to Christ and His Mother. The Fijian crew traced the sign of the Cross with the quiet faith of people who understand the ways of the sea. The storm continued, and through the grey, a dark line slowly formed. Land.

As the boat neared the beach, outlines sharpened into trees and the shoreline. When they finally stepped onto the sand, the village welcomed them with songs, garlands and open arms. Children ran to embrace them. The journey across dangerous water and the warmth of the welcome revealed a single truth. Human life rests within forces larger than our strength and is held in a love deeper than fear.

The modern world also moves like the waves of the ocean. It offers abundance, stimulation and endless activity, and many hearts carry a quiet exhaustion. In pastoral life this appears when people speak of scattered prayer, restless evenings and burdens that multiply faster than the soul can absorb. Some describe having everything they once wanted while sensing an inner thinning that leaves them unsettled. The heart was shaped for grace, not for relentless strain. When stretched beyond its measure, it cannot contain everything. It begins to overflow, but not with grace.

Christ speaks directly to this hidden fatigue when He blesses the poor in spirit (Matthew 5.3). Poverty of spirit is an inner spaciousness. It is the awareness that the heart flourishes when it receives rather than grasps, when it sits open rather than crowded. The Fathers call the heart a vessel created to carry divine life. Saint Isaac the Syrian teaches that grace settles in the heart that releases its grip on its own strength. Saint Basil reminds believers that even the desire for holiness grows beautifully when the heart becomes light and uncluttered.

Christ says, “Come to Me, all you who labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11.28). He fills the space that humility opens.

Zacchaeus shows this freedom. He climbs the sycamore tree for clarity without closeness (Luke 19.1 to 10). Christ calls him to come down. That descent becomes his salvation. Zacchaeus returns to the ground, opens his home and the Lord enters. The blessing for the poor in spirit becomes real. The kingdom draws near to the man who comes down from his own sycamore tree.

The Theotokos teaches this readiness. Her words, “Let it be to me according to your word” (Luke 1.38), reveal the posture of the open heart. She offers not strategy but availability. Her humanity becomes the vessel through which God enters the world. When the missionaries prayed upon that small boat, they turned to her, as Christians have done throughout centuries, asking for strength that flows from trust. Wherever the Orthodox mission is alive this Marian “Let it be..” quietly repeats itself in the lives of ordinary people who open their homes, their time and their wounds to Christ.

Christ reveals the same truth in other Gospel scenes. The land of a rich man produces plentifully (Luke 12.16 to 21). He expands his barns but overlooks the life of the soul. His days fill with accumulation, yet the deeper spaces of the heart remain untouched by grace. In many societies a similar pattern emerges. Lives are full of movement but thin in inner stillness. Activity multiplies, joy fades and prayer feels distant.

Another Gospel scene shows the same spiritual condition in a different way. The paralytic of Capernaum is lowered through the roof by friends (Mark 2.1 to 12). His healing begins with surrender. Christ first speaks forgiveness. The Fathers teach that forgiveness straightens the soul where sin has bent it. The hole in the roof becomes a doorway for grace. Saint Gregory Palamas explains that God sometimes allows disruption so that hidden wounds can be reached by divine healing. The paralytic shows what happens when the heart no longer tries to rise by its own power but looks to Christ with trust to be lifted.

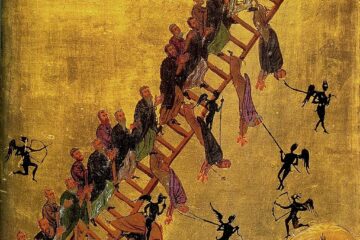

These scriptures reflect the experience of many today. People climb invisible ladders seeking stability and often feel more divided the higher they climb. Time becomes something to guard rather than share. Life feels like a performance rather than a gift. Saint Paul speaks of the world pressing its form upon the mind and urges believers not to be conformed to this age but to be transformed by the renewing of the mind (Romans 12.2).

Against this landscape, the Orthodox mission in Fiji reveals a different rhythm. In the villages, life unfolds with simplicity and depth. Homes are modest, but hearts are open. Visitors are welcomed with gratitude shaped by relationship rather than excess. Time is shared, not defended. Identity flows from belonging. Personhood grows in communion.

Here the Fijian sense of vanua, the unity of people, land and story, echoes the Christian understanding of the Church. A person discovers who they are through relationship, culminating in belonging to Christ and His Body. “Now you are the body of Christ and members individually” (1 Corinthians 12.27). Belonging becomes the atmosphere of life not an idea.

One experience from the early years of the mission expresses this difference with particular force. The storm on the small boat, the whispered prayers, the trust in the Mother of God, and then the welcome on the shore of Sophronia’s village, all revealed that life is held in a communion that goes beyond our plans. The journey to that little koro required risk, physical effort, and trust. The last part was not made on a large ship but on that open vessel that fought its way through waves and wind. The missionaries saw with their own eyes how fragile their work was. Yet when they arrived, the village stood ready, with songs already on their lips. It was as if the Gospel had reached the vanua before them and had been waiting for them to step onto the sand.

This anthropology of belonging appears throughout the mission. In Savudrodro, the team once walked along the road seeking a small Orthodox family. Before they could call out, a voice from the hillside shouted, “Father Michael.” Phanourios came running barefoot, tears flowing. The embrace was not simply emotional. It was ecclesial. Saint Paul’s teaching that in Christ believers are “members of the household of God” (Ephesians 2.19) became visible in that moment. Mission emerged as family recognising family, veiwekani restored in Christ.

Another moment unfolded near Labasa. Chairs were already arranged in a gentle semicircle, a table prepared with a cloth, a candle and a simple icon. Hibiscus petals were scattered with care. No message had confirmed the time. The family simply rose early in faith. After the prayers the father said, “This morning I asked God to visit our house. When you came, I knew He had answered.” His words revealed a heart ready for Christ, echoing Saint Paul’s prayer that Christ may dwell within the inner person through faith (Ephesians 3.16 to 17).

Many homes in the West offer space without rest. People share a roof yet feel distant. Houses are larger, but space is filled with screens and schedules. Families can live under one roof yet feel like strangers to one another. The house becomes a place of constant movement, noise, and distraction. It offers shelter to the body, but not always rest to the soul. A person can move from bedroom to car to office to lounge chair without ever feeling that they have arrived home in the deeper sense. In Fijian homes, presence fills the rooms. The home becomes a place of shared life, prayer and welcome. The vanua enters the home and the home is lifted to God. When a family prays, their yalo, their inner life, is not a hidden private space. It is drawn into the shared life of the village and the Church.

This shared life shines especially during hardship. When strong winds damaged houses, villagers gathered the next morning. Men secured roofs, children carried timber, mothers cooked for everyone and elders prayed. They moved as one body. Saint Paul’s call to bear one another’s burdens (Galatians 6.2) was already woven into their way of life. It was a description of what already existed, an echo of the life of the first Christians in Acts, who shared what they had and broke bread together with gladness of heart (Acts 2.42–47).

In such a setting, the sacramental life does not appear as an addition to ordinary life but as its heart. Baptisms take place in simple fonts, sometimes under open sky, where the water reflects the clouds and the light. Those who come out of the water do not simply join an institution. They begin to live from a different centre. Their sense of self is reshaped. They know themselves as children of God and members of a community that extends far beyond their village, a community that includes the saints and the faithful in every land. “If anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation” (2 Corinthians 5.17). In Fijian terms, their vakabauta, their faith, is now woven into a wider veilomani, a mutual love, that reaches from their koro to the whole Church.

The Divine Liturgy reflects the same reality. In chapels of timber and tin, or in small churches built through countless quiet sacrifices, the people gather without show. Children watch their parents cross themselves and bow. Young men stand quietly at the back or help at the chant stand. Women sing with gentle strength. The chanting may not be polished, but it rises from sincerity. The silence before Holy Communion has a depth that words cannot describe. People approach the chalice with the awareness that Christ is not a symbol but a presence.

Saint Nicholas Cabasilas teaches that the Eucharist restores the image of God in the believer. In Fiji, this restoration can be seen on the faces of those who return from the chalice. Their expressions soften. Anxiety loosens. The eyes become more transparent. The Fathers say that the heart is a small place, yet it can hold God. Saint Makarios of Egypt writes that within the heart there are lions and dragons, but there too is God and the angels. In these village churches, this teaching ceases to be only an image. The heart revealed in worship is truly a place where heaven and earth meet. The vessel of the heart receives Christ, and in time it begins to pour out His peace to others

Confession also takes on a distinctive character in this environment. It often happens under a tree, beside a river, or in a quiet corner away from the others. A father may speak about his anger, his financial pressures, and his fear for his children. He may confess that he has become harsh at home, that he does not know how to carry everything on his own. The talanoa, the deep and honest conversation that is part of Fijian culture, becomes prayer. When absolution is given, he will sometimes say that a weight has left him. Saint John Chrysostom describes repentance as the removal of the heaviness that obstructs the soul. In the Pacific, the connection between repentance and freedom is not analysed. It is experienced. The heart that was bent inward begins to straighten again toward God.

From this sacramental centre, mission flows as something natural. The Gospel is not pushed forward by strategies or slogans. It passes from person to person like a flame passed from one candle to another in the stillness of Pascha night. Families that have received mercy become merciful. Homes that have known blessing become places where others find rest. A grandmother who prays the psalms in the evening brings the whole household into a gentle awareness of God. A young man who has learned to chant in church begins to teach the younger boys, not because he was appointed to do so, but because it feels right. The vessel of the heart receives, and then it pours.

This reveals something of how the Gospel shapes human identity. In many Western societies, the self is imagined as an isolated centre of choice that must construct its own meaning. A person must decide who they are, display it, and defend it. In the Pacific, the self is discovered in belonging. A person knows who he or she is because of family, village, land, and now Church. When Orthodoxy arrives in such a culture, it does not erase this sense of belonging. It fulfils it. It shows that the deepest community is the Body of Christ, and that every village Liturgy stands in communion with the Liturgy of the entire Church. The vanua finds its true horizon in the Kingdom.

The story of the first Orthodox communities in Fiji illustrates this. When Metropolitan Amphilochios first travelled to Vanua Levu, he encountered people like Pantelis Baravilala and Sophronia, whose hearts were already open to Christ. Travel to their village involved risk, effort, and trust. Again the last part of the journey to Sophronia’s island was made not on a large ship but on a small, open boat that fought its way through waves and wind. The missionaries saw how fragile their plans were. Yet when they arrived, they were met by a community that was ready to receive the Gospel as something long awaited, as if it completed what was already present in their sense of vanua, their relationship with land and each other.

In Labasa, the small church of Saints Athanasios and Nicholas began as a humble chapel. It became a centre of faith where families travelled long distances to gather in joy. Their veilomani, their love for one another, grew at the chalice and shaped their whole life.

In all these examples, the vessel of the heart is not forced to carry everything alone. Life is carried together. This has deep consequences for how people experience God. When a mother in Fiji prays for her children, she knows that others are praying with her. When a young man struggles, he does not simply look inward. He looks to his priest, to his elders, to his fellow believers. The heart learns to be open because it has not been trained to be isolated.

This is why joy remains one of the most persuasive signs of the Gospel in the Pacific. Not excitement that fades, not sentiment, but the quiet, steady joy that Saint Ephraim describes as the fragrance of the soul visited by the Holy Spirit. It appears in children who chant eagerly, in elders who bow with dignity, in families who gather after a long day of work to give thanks, in the songs offered by the children of Saint Tabitha’s Orphanage as they dance in gratitude under the evening sky. This joy does not ignore suffering. It coexists with it and even grows through it. It is the joy of those who know that they are not alone, that Christ has entered their homes, and that His presence brings peace. It echoes the promise of the Lord, “that My joy may remain in you, and that your joy may be full” (John 15.11).

You may never visit Fiji. Your daily life may unfold in a city far from the Pacific, in a flat above a noisy street or in a house that feels more like a station than a home. Yet the same Gospel speaks to you. The same Christ waits at the door of your heart. The practices that have taken root in the koro can quietly shape life in a suburb or a village in another country. A small corner of a room can become a place of prayer. A simple candle before an icon of Christ or His Mother can remind a family that their true centre is not the screen but the altar of the heart. A shared meal with another household, a few minutes of family prayer in the evening, a word of forgiveness before sleep, all become ways in which the vessel of the heart begins to empty itself of fear, anxiety, pride and fill itself with grace.

The Orthodox mission in Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa shows that the Gospel does not require ideal circumstances. It asks for open hearts. It flourishes where people allow their sense of self to be reshaped by Christ, where time is offered rather than guarded, where homes become places of prayer and welcome. The Pacific teaches that poverty of spirit is not weakness but freedom. It frees the heart from the illusion that it must hold everything together. It teaches the soul to say with the Theotokos, “Let it be to me according to your word”. When that is whispered in a hut beneath palm trees or in a flat in a crowded city, the same grace descends.

In a world that often forms people into isolated individuals with crowded hearts, the Pacific offers another witness. It shows that true humanity is found in communion, that the heart becomes itself when it learns to belong, and that mission is not an external project but the overflow of a Eucharistic life. The vessel receives and then pours. The more it empties itself of fear, pride, and self reliance, the more it is filled with Christ. From that fullness, grace flows outward to children, families, villages, and beyond the islands themselves, to every place where people long for peace.

The world continues to hunger for such witnesses. The Church is called to offer them with humility and love. Wherever Christ is welcomed in this way, salvation follows. Not only as an outer event, but as a quiet, deep transformation of the human heart and of the way people live together. Under the Southern Cross and in every land, the same Lord waits to be received. The same Christ who calmed the storm on the Sea of Galilee watches over small boats on the Pacific and over the hidden storms in the human heart. The vessel of the heart need only open, and He will enter.

*****

Fr Michael is a priest of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia. He has studied Information Technology, Modern Greek, and Theology at Flinders University. With a deep love for music, theology, and arts Fr Michael brings a dynamism to his ministry.

Fr Michael is a priest of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia. He has studied Information Technology, Modern Greek, and Theology at Flinders University. With a deep love for music, theology, and arts Fr Michael brings a dynamism to his ministry.

His 13 year ministry has included service in aged care, the youth, regional communities, and meeting the needs of busy Parishes with Presvytera Stavroula.

Fr Michael is also actively involved in Orthodox missionary outreach in the Pacific, particularly in Fiji. He has spent time in the region serving liturgy, engaging with local communities, and working towards the development of the mission.

He is currently serving at the Parish of St Dimitrios, Salisbury, in South Australia.

0 Comments