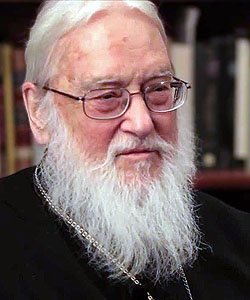

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware of Diokleia

Sharing, Silence, Suffering

If the Mother of God at the moment of the Annunciation is a true icon of human freedom, of authentic liberty and liberation, then her actions and reactions in the events that follow shortly afterwards in St. Luke’s Gospel illustrate three basic consequences of what it means to be free. Freedom involves sharing, silence, and suffering.

Sharing

Freed om involves sharing. Mary’s first action after the Annunciation is to share the good news with someone else: she goes with haste to the hill country, to the house of Zechariah, and greets her cousin Elizabeth.[8] Here is an essential element in freedom: you cannot be free alone. Freedom is not solitary but social. It implies relationship, a “thou” [You] as well as an “I.” The one who is egocentric, who repudiates all responsibility towards others, possesses no more than a seeming and spurious freedom, but is in reality pitifully unfree. Liberation, properly understood, is not defiant isolation or aggressive self-assertion, but partnership and solidarity. To be free is to share our personhood with others, to see with their eyes, to feel with their feelings: “If one member of the body suffers, all suffer together with it.”[9] I am only free if I become a prosopon—to use the Greek word for person which literally means “face”—if I turn towards others, looking into their eyes and allowing them to look into mine. To turn away, to refuse to share, is to forfeit liberty.

om involves sharing. Mary’s first action after the Annunciation is to share the good news with someone else: she goes with haste to the hill country, to the house of Zechariah, and greets her cousin Elizabeth.[8] Here is an essential element in freedom: you cannot be free alone. Freedom is not solitary but social. It implies relationship, a “thou” [You] as well as an “I.” The one who is egocentric, who repudiates all responsibility towards others, possesses no more than a seeming and spurious freedom, but is in reality pitifully unfree. Liberation, properly understood, is not defiant isolation or aggressive self-assertion, but partnership and solidarity. To be free is to share our personhood with others, to see with their eyes, to feel with their feelings: “If one member of the body suffers, all suffer together with it.”[9] I am only free if I become a prosopon—to use the Greek word for person which literally means “face”—if I turn towards others, looking into their eyes and allowing them to look into mine. To turn away, to refuse to share, is to forfeit liberty.

Here the Christian doctrine of God is immediately relevant to our understanding of freedom. As Christians we believe in a God who is not only one but one in three. The divine image within us is specifically the image of God the Trinity. God our creator and archetype is not just one person, self-sufficient, loving Himself alone, but He is a koinonia or communion of three persons, dwelling in each other through an unceasing movement of mutual love. From this it follows that the divine image within us, which is the uncreated source of our freedom, is a relational image, realized through fellowship and perichoresis (intermingling). To say, “I am free, because I am formed in God’s image,” is equivalent to saying: “I need you in order to be myself.” There is no true person except where there are at least two persons in reciprocal relationship; and there is no true freedom except where there are at least two persons who share their freedom together.

Here, then, is a first thing that Mary teaches us about freedom. It signifies relationship, openness to others, vulnerability. Without the risk and adventure of shared love, none of us can be free.

Silence

If freedom involves sharing, then it also involves silence, listening. “Let it be with me according to your word,” Mary answers at the Annunciation; her attitude is one of listening to the Word of God. Indeed, had she not first listened to God’s Word and through listening received it into her heart, she would never have conceived and borne the Word physically in her womb. St. Luke insists more than once upon this special characteristic of the Mother of God as the one who listens. After the visit of the shepherds to the newborn Christ, he states; “Mary treasured all these words and pondered them in her heart.”[10] After the story of Jesus in the temple at twelve years old, the evangelist ends with a similar comment: “His Mother treasured all these things in her heart.”[11] The need to listen is emphasized equally in Mary’s injunction to the servants at the wedding feast of Cana, “Do whatever He tells you,”[12] her last recorded words in the Gospels, her spiritual legacy to the Church: “Listen, accept, respond.” Later in St. Luke’s Gospel—when the woman in the crowd blesses Christ’s Mother, and He replies, “Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and obey it”[13]—so far from implying any disrespect to the one who bore Him,

Theotokos (Mother of God), tempera on wood, Holy Mountain Athos, 17th Century

Jesus seeks rather to indicate where her true glory is to be found. She is to be held in honor, not simply because of the physical fact of her motherhood, but because inwardly with all her will and with the full integrity of her personal freedom she listened to God’s word and kept it.

Such, therefore, is a second way in which the Mother of God acts as an icon of human freedom. For St. Gregory Palamas and for the Orthodox mystical tradition she is ahesychast, one who waits upon the Holy Spirit with the silence of the heart. Inner silence of this kind is not simply negative—not a mere absence of sounds or pause between words—but it is positive and alive, one of the deep sources of our being, part of the basic structure of our human personhood. Without silence we are not genuinely human, and without silence we are not genuinely free. Constant chatter enslaves, while the ability to listen is an essential part of freedom. The Mother of God is free because she listens. Unless we are capable of listening to others—unless in some measure we possess, as she did, the dimension of creative inner silence—we shall lack real liberty. Only the one who knows how to be silent, how to listen, is able to make decisions with an authentic freedom of choice.

Suffering

There is also a third aspect of freedom that St. Luke’s Gospel underlines. “A sword will pierce through your own soul also,”[14] says Simeon to Mary at the Presentation of Christ in the Temple. Freedom involves suffering. It means kenosis (emptying oneself), cross-bearing, the laying down of one’s own life for the sake of others. Mary’s act of voluntary choice at the Annunciation brings her grief as well as joy. Among modern thinkers, the Russian Nicholas Berdyaev—the “captive of freedom,” as his critics called him, a sobriquet (nickname) that gave him particular satisfaction—has discerned with sharp clarity the costliness of freedom. “I always knew,” he states in his autobiography, Dream and Reality, “that freedom gives birth to suffering, while the refusal to be free diminishes suffering. Freedom is not easy, as its enemies and slanderers allege: freedom is hard; it is a heavy burden. People…often renounce freedom to ease their lot.”[15]

The arduous, sacrificial character of freedom is evident equally in Dostoevsky’s parable “The Tale of the Grand Inquisitor” in The Brothers Karamazov. The inquisitor reproaches Christ for making humankind free, and thereby imposing on them a pain too sharp for them to endure. Out of pity for human anguish, so the inquisitor claims, he and his fellows have removed this cruel gift of freedom: “We have corrected your work,” he says to Christ. He is right: freedom is indeed a heavy burden, as Mary understood only too well when standing at the foot of the Cross. Yet without freedom there can be no true personhood and no mutual love. If we refuse to exercise the gift of freedom that God offers us, we make ourselves subhuman; and if we deny others their freedom we dehumanize them.

Such are some of the ways in which the Mother of God, our mirror and paradigm, serves as an icon of human freedom. “Am I not free?” Yes, indeed; each of us is created free. Yet freedom is not only a gift but equally a challenge and a task, as the example of the Mother of God indicates. Freedom does not simply have to be accepted, but it needs to be discovered, learnt, used, defended—and finally to be offered up. Let us complete the quotation from Kierkegaard with which we began. “The most tremendous thing granted to human persons is choice, freedom. And if you want to save your freedom and keep it, there is only one way: in the very same second to give it back to God, and yourself with it.” Only in the act of offering back our freedom to God—through sharing, silence, and suffering—can we truly become free persons in the image of the Trinity, after the example of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

8. Luke 1:39-40.

9. 1 Corinthians 12:26.

10. Luke 2:19.

11. Luke 2:51.

12. John 2:5.

13. Luke 10:27-28.

14. Luke 2:35.

15. P. 47.

First part here

Source: pemptousia.com

0 Comments