Fr. Lev Gillet*

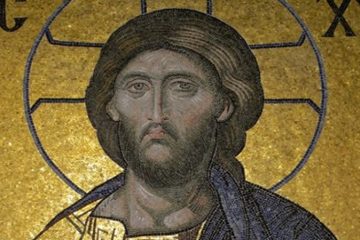

Epiphany was the first public manifestation of Christ. At the time of His birth, our Lord was revealed to a few privileged people. Today, all those who surround John, that is to say his own disciples and the crowd that has come to the banks of the Jordan, witness a more solemn manifestation of Jesus Christ. What does this manifestation consist of? It is made up of two aspects. On the one hand there is the humility, represented by the baptism to which our Lord submits: on the other hand, there is the aspect of glory represented by the human witness that the Precursor bears to Jesus, and, on an infinitely higher plane, the divine witness which the Father and the Spirit bear to the Son. We shall look at these aspects more closely. But first of all, let us bear this in mind: every manifestation of Jesus Christ, both in history and in the inner life of each man, is simultaneously a manifestation of humility and of glory. Whoever tries to separate these two aspects of Christ commits an error which falsifies the whole of spiritual life. I cannot approach the glorified Christ without, at the same time, approaching the humiliated Christ, nor the humiliated Christ without approaching the glorified Christ. If I desire Christ to be manifested in me, in my life, this cannot come about except through embracing him, whom Augustine delighted to call Christus humilis, and, in the same upsurge, worshipping him who is also God, King and Conqueror. This is the first lesson of Epiphany.

The aspect of humility in Epiphany consists of the fact that Our Lord submits to John’s baptism of repentance. John himself refuses to begin with, but Jesus insists: ‘Suffer it to be so now; for thus it becometh us to fulfil all righteousness’ [Matth. 3, 13-15]. Obviously Jesus had no need to be purified by John, but this baptism conferred by the Precursor, this baptism for the remission of sins, was a preparation for the messianic kingdom; and Jesus, before proclaiming the coming of this kingdom, wished to go through all those preparatory phases which he himself was to ‘consummate’. Being himself the fulness, he wished to take into himself all that was still incomplete and unfinished. But in receiving the Johannine baptism, Jesus did more than solemnly approve and confirm a rite before transforming it – more than consummate the imperfect into the perfect. He who was without sin made himself the bearer of all our sins, of the sin of the whole world; and it is in the name of all sinners that Jesus made a public act of repentance. Moreover, Jesus wished to teach us the necessity of patience and conversion; before we can draw near to Christian baptism itself, we must receive John’s baptism, that means we have to go through a change of spirit, through an inner catastrophe. We must experience real contrition for our sinfulness. As far as we ourselves are concerned, repentance is the aspect of humility in Epiphany. And here we must go beyond the limited horizon of the Johannine baptism and remind ourselves that we have been baptised in Christ. Christian baptism has washed and purified us. It has abolished original sin** in us and made a new creature of us. We were probably infants when we were baptized; baptismal grace was then a divine response, not to our personal request, but to the faith of those who brought us to baptism and also to the faith of the whole Church when it accepted us. This baptismal grace was, then, in some way provisional and conditional: it needed us, of our own free choice as we grew up and became conscious, to confirm the act of our baptism, not only of Jesus’s baptism, but also of our own. It is a wonderful opportunity for us to revive the grace which was conferred on us. For the sacramental graces, even if interrupted and suspended by sin, can become alive in us again, if we turn sincerely to God. At this feast of Epiphany, let us ask God to wash us again – spiritually, not actually – in the waters of baptism; let us drown the old, the sinful, creature in them, for baptism is a mystical death; let us cross the Red Sea which separates captivity from freedom and let us immerse ourselves with Jesus in the Jordan to be washed not by the Precursor but by Jesus himself.

(to be continued)

*Fr. Lev Gillet. Born in France and initially a member of the Church of Rome, he became interested in Orthodoxy as a young man when he was posted to the front in World War I and came across Russian soldiers in his role as a liaison officer. After training as a scientist at university, he was received into the Orthodox Church in 1928, at the age of thirty-five. After being appointed rector of the first French-speaking Orthodox parish of Sainte-Geneviève-de-Paris, he went on to work in England and the Lebanon.

** Fr. Lev wrote in French. I do not have access to the French text, so it is not possible to say whether he wrote ‘original sin’ or whether this is the translator’s rendition. In Orthodoxy, we understand that we bear the consequence of the first sin, i.e. death, but that we’re not guilty of having committed it. WJL.

Source: pemptousia.com

0 Comments